Pineapple

The pineapple (Ananas comosus) is a tropical plant with an edible multiple fruit consisting of coalesced berries, also called pineapples, and the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae.

Pineapples may be cultivated from the offset produced at the top of the fruit, possibly flowering in five to ten months and fruiting in the following six months. Pineapples do not ripen significantly after harvest.In 2016, Costa Rica, Brazil, and the Philippines accounted for nearly one-third of the world's production of pineapples.

Compared to other countries the ghanaian pineapple is cultivated gently. Preparing plots take place on a naturally way. Tropigha Frams grows the varities MD2, Sugar Loaf and Queen Victoria as well as baby-pines. Sugar Loaf and Queen Victoria are growing as organic fruits.

Botany

The pineapple is a herbaceous perennial, which grows to 1.0 to 1.5 m (3.3 to 4.9 ft) tall, although sometimes it can be taller. In appearance, the plant has a short, stocky stem with tough, waxy leaves. When creating its fruit, it usually produces up to 200 flowers, although some large-fruited cultivars can exceed this. Once it flowers, the individual fruits of the flowers join together to create what is commonly referred to as a pineapple. After the first fruit is produced, side shoots (called 'suckers' by commercial growers) are produced in the leaf axils of the main stem. These may be removed for propagation, or left to produce additional fruits on the original plant.[5] Commercially, suckers that appear around the base are cultivated. It has 30 or more long, narrow, fleshy, trough-shaped leaves with sharp spines along the margins that are 30 to 100 cm (1.0 to 3.3 ft) long, surrounding a thick stem. In the first year of growth, the axis lengthens and thickens, bearing numerous leaves in close spirals. After 12 to 20 months, the stem grows into a spike-like inflorescence up to 15 cm (6 in) long with over 100 spirally arranged, trimerous flowers, each subtended by a bract. Flower colors vary, depending on variety, from lavender, through light purple to red.[citation needed]

The ovaries develop into berries, which coalesce into a large, compact, multiple fruit. The fruit of a pineapple is arranged in two interlocking helices, eight in one direction, 13 in the other, each being a Fibonacci number.

The pineapple carries out CAM photosynthesis, fixing carbon dioxide at night and storing it as the acid malate, then releasing it during the day aiding photosynthesis.

Culinary uses

The flesh and juice of the pineapple are used in cuisines around the world. In many tropical countries, pineapple is prepared and sold on roadsides as a snack. It is sold whole or in halves with a stick inserted. Whole, cored slices with a cherry in the middle are a common garnish on hams in the West. Chunks of pineapple are used in desserts such as fruit salad, as well as in some savory dishes, including pizza toppings, or as a grilled ring on a hamburger. Crushed pineapple is used in yogurt, jam, sweets, and ice cream. The juice of the pineapple is served as a beverage, and it is also the main ingredient in cocktails such as the piña colada and in the drink tepache.

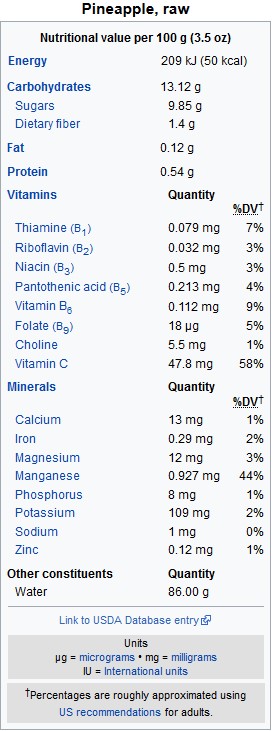

Nutrition

In a 100-gram reference amount, raw pineapple is a rich source of manganese (44% Daily Value, DV) and vitamin C (58% DV), but otherwise contains no essential nutrients in significant quantities

Bromelain

Present in all parts of the pineapple plant,bromelain is a mixture of proteolytic enzymes. Bromelain is under preliminary research for a variety of clinical disorders, but to date has not been adequately defined for its effects in the human body. Bromelain may be unsafe for some users, such as in pregnancy, allergies, or anticoagulation therapy.

If having sufficient bromelain content, raw pineapple juice may be useful as a meat marinade and tenderizer. Although pineapple enzymes can interfere with the preparation of some foods or manufactured products, such as gelatin-based desserts or gel capsules, their proteolytic activity responsible for such properties may be degraded during cooking and canning. The quantity of bromelain in a typical serving of pineapple fruit is probably not significant, but specific extraction can yield sufficient quantities for domestic and industrial processing.

The bromelain content of raw pineapple is responsible for the sore mouth feeling often experienced when eating it, due to the enzymes breaking down the proteins of sensitive tissues in the mouth. Also, raphides, needle-shaped crystals of calcium oxalate that occur in pineapple fruits and leaves, likely cause microabrasions, contributing to mouth discomfort.

Ethical and environmental concerns

Three-quarters of the pineapples sold in Europe are grown in Costa Rica, where pineapple production is highly industrialised. Growers typically use 20 kg (44 lb) of pesticides per hectare in each growing cycle, a process that may affect soil quality and biodiversity. Compared to these the former domestic varities of pineappple only need 10% of today use vloume of pesticides. The pesticides—organophosphates, organochlorines, and hormone disruptors—have the potential to affect workers' health and can contaminate local drinking water supplies. Many of these chemicals have potential to be carcinogens, and may be related to birth defects.

Because of commercial pressures, many pineapple workers—60% of whom are Nicaraguan—in Costa Rica are paid low wages. European supermarkets' price-reduction policies have lowered growers' incomes. One major pineapple producer contests these claims.

Papaya

The papaya from Carib via Spanish), papaw, or pawpaw is the plant Carica papaya, one of the 22 accepted species in the genus Carica of the family Caricaceae. Its origin is in the tropics of the Americas, perhaps from southern Mexico and neighboring Central America.

Description

The papaya is a small, sparsely branched tree, usually with a single stem growing from 5 to 10 m (16 to 33 ft) tall, with spirally arranged leaves confined to the top of the trunk. The lower trunk is conspicuously scarred where leaves and fruit were borne. The leaves are large, 50–70 cm (20–28 in) in diameter, deeply palmately lobed, with seven lobes. All parts of the plant contain latex in articulated laticifers. Papayas are dioecious. The flowers are 5-parted and highly dimorphic, the male flowers with the stamens fused to the petals. The female flowers have a superior ovary and five contorted petals loosely connected at the base. Male and female flowers are borne in the leaf axils, the males in multiflowered dichasia, the female flowers is few-flowered dichasia. The flowers are sweet-scented, open at night and are moth-pollinated. The fruit is a large berry about 15–45 cm (5.9–17.7 in) long and 10–30 cm (3.9–11.8 in) in diameter. It is ripe when it feels soft (as soft as a ripe avocado or a bit softer) and its skin has attained an amber to orange hue.

Origin and distribution

Native to Mexico and northern South America, papaya has become naturalized throughout the Caribbean Islands, Florida, Texas, California, Hawaii, and other tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Cultivation

Papaya plants grow in three sexes: male, female, hermaphrodite. The male produces only pollen, never fruit. The female will produce small, inedible fruits unless pollinated. The hermaphrodite can self-pollinate since its flowers contain both male stamens and female ovaries. Almost all commercial papaya orchards contain only hermaphrodites.

Originally from southern Mexico (particularly Chiapas and Veracruz), Central America, and northern South America, the papaya is now cultivated in most tropical countries. In cultivation, it grows rapidly, fruiting within three years. It is, however, highly frost-sensitive, limiting its production to tropical climates. Temperatures below −2 °C (29 °F) are greatly harmful if not fatal. In Florida, California, and Texas, growth is generally limited to southern parts of the states. It prefers sandy, well-drained soil, as standing water will kill the plant within 24 hours.

For cultivation, however, only female plants are used, since they give off a single flower each time, and close to the base of the plant, while the male gives off multiple flowers in long stems, which result in poorer quality fruit.

Cultivars

Two kinds of papayas are commonly grown. One has sweet, red or orange flesh, and the other has yellow flesh; in Australia, these are called "red papaya" and "yellow papaw", respectively. Either kind, picked green, is called a "green papaya".

The large-fruited, red-fleshed 'Maradol', 'Sunrise', and 'Caribbean Red' papayas often sold in U.S. markets are commonly grown in Mexico and Belize.

In 2011, Philippine researchers reported that by hybridizing papaya with Vasconcellea quercifolia, they had developed conventionally bred, nongenetically engineered papaya resistant to PRV.

Carica papaya was the first transgenic fruit tree to have its genome sequenced. In response to the papaya ringspot virus (PRV) outbreak in Hawaii, in 1998, genetically altered papaya were approved and brought to market (including 'SunUp' and 'Rainbow' varieties.) Varieties resistant to PRV have some DNA of this virus incorporated into the DNA of the plant. As of 2010, 80% of Hawaiian papaya plants were genetically modified. The modifications were made by University of Hawaii scientists who made the modified seeds available to farmers without charge.

Diseases and pests

Viruses

Papaya ringspot virus is a well-known virus within plants in Florida. The first signs of the virus are yellowing and vein-clearing of younger leaves, as well as mottling yellow leaves. Infected leaves may obtain blisters, roughen or narrow, with blades sticking upwards from the middle of the leaves. The petioles and stems may develop dark green greasy streaks and in time become shorter. The ringspots are circular, C-shaped markings that are darker green than the fruit itself. In the later stages of the virus, the markings may become gray and crusty. Viral infections impact growth and reduce the fruit's quality. One of the biggest effects that viral infections have on papaya is the taste. As of 2010, the only way to protect papaya from this virus is genetic modification.

The papaya mosaic virus destroys the plant until only a small tuft of leaves are left. The virus affects both the leaves of the plant and the fruit. Leaves show thin, irregular, dark-green lines around the borders and clear areas around the veins. The more severely affected leaves are irregular and linear in shape. The virus can infect the fruit at any stage of its maturity. Fruits as young as 2 weeks old have been spotted with dark-green ringspots about 1 inch in diameter. Rings on the fruit are most likely seen on either the stem end or the blossom end. In the early stages of the ringspots, the rings tend to be many closed circles, but as the disease develops, the rings will increase in diameter consisting of one large ring. The difference between the ringspot and the mosaic viruses is the ripe fruit in the ringspot has mottling of colors and mosaic does not.

Fungi

The fungus anthracnose is known to specifically attack papaya, especially the mature fruits. The disease starts out small with very few signs, such as water-soaked spots on ripening fruits. The spots become sunken, turn brown or black, and may get bigger. In some of the older spots, the fungus may produce pink spores. The fruit ends up being soft and having an off flavor because the fungus grows into the fruit.

The fungus powdery mildew occurs as a superficial white presence on the surface of the leaf in which it is easily recognized. Tiny, light yellow spots begin on the lower surfaces of the leaf as the disease starts to make its way. The spots enlarge and white powdery growth appears on the leaves. The infection usually appears at the upper leaf surface as white fungal growth. Powdery mildew is not as severe as other diseases.

The fungus phytophthora blight causes damping-off, root rot, stem rot, stem girdling, and fruit rot. Damping-off happens in young plants by wilting and death. The spots on established plants start out as white, water-soaked lesions at the fruit and branch scars. These spots enlarge and eventually cause death. The most dangerous feature of the disease is the infection of the fruit which may be toxic to consumers. The roots can also be severely and rapidly infected, causing the plant to brown and wilt away, collapsing within days.

Pests

The papaya fruit fly lays its eggs inside of the fruit, possibly up to 100 or more eggs. The eggs usually hatch within 12 days when they begin to feed on seeds and interior parts of the fruit. When the larvae mature usually 16 days after being hatched, they eat their way out of the fruit, drop to the ground, and pupate in the soil to emerge within one to two weeks later as mature flies. The infected papaya will turn yellow and drop to the ground after infestation by the papaya fruit fly.

The two-spotted spider mite is a 0.5-mm-long brown or orange-red or a green, greenish yellow translucent oval pest. They all have needle-like piercing-sucking mouthparts and feed by piercing the plant tissue with their mouthparts, usually on the underside of the plant. The spider mites spin fine threads of webbing on the host plant, and when they remove the sap, the mesophyll tissue collapses and a small chlorotic spot forms at the feeding sites. The leaves of the papaya fruit turn yellow, gray, or bronze. If the spider mites are not controlled, they can cause the death of the fruit.

The papaya whitefly lays yellow, oval eggs that appear dusted on the undersides of the leaves. They eat papaya leaves, therefore damaging the fruit. There, the eggs developed into flies in three stages called instars. The first instar has well-developed legs and is the only mobile immature life stage. The crawlers insert their mouthparts in the lower surfaces of the leaf when they find it suitable and usually do not move again in this stage. The next instars are flattened, oval, and scale-like. In the final stage, the pupal whiteflies are more convex, with large, conspicuously red eyes.

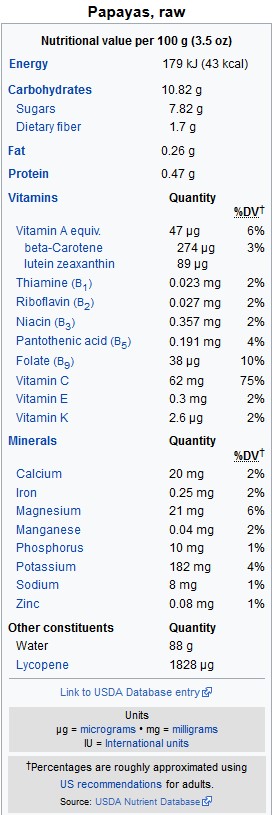

Nutrition

Raw papaya pulp contains 88% water, 11% carbohydrates, and negligible fat and protein (table). In a 100 gram amount, papaya fruit provides 43 kilocalories and is a significant source of vitamin C (75% of the Daily Value, DV) and a moderate source of folate (10% DV), but otherwise has low content of nutrients.

Culinary uses

The ripe fruit of the papaya is usually eaten raw, without skin or seeds. The unripe green fruit can be eaten cooked, usually in curries, salads, and stews. Green papaya is used in Southeast Asian cooking, both raw and cooked. In Thai cuisine, papaya is used to make Thai salads such as som tam and Thai curries such as kaeng som when still not fully ripe. In Indonesian cuisine, the unripe green fruits and young leaves are boiled for use as part of lalab salad, while the flower buds are sautéed and stir-fried with chillies and green tomatoes as Minahasan papaya flower vegetable dish. Papayas have a relatively high amount of pectin, which can be used to make jellies. The smell of ripe, fresh papaya flesh can strike some people as unpleasant. In Brazil, the unripe fruits are often used to make sweets or preserves.

The black seeds of the papaya are edible and have a sharp, spicy taste. They are sometimes ground and used as a substitute for black pepper.

In some parts of Asia, the young leaves of the papaya are steamed and eaten like spinach.

Meat tenderizing

Both green papaya fruit and the plant's latex are rich in papain, a protease used for tenderizing meat and other proteins, as practiced currently by indigenous Americans and people of the Caribbean region. It is now included as a component in some powdered meat tenderizers.

Phytochemicals

Papaya skin, pulp and seeds contain a variety of phytochemicals, including carotenoids and polyphenols,[26] as well as benzyl isothiocyanates and benzyl glucosinates, with skin and pulp levels that increase during ripening.[27] Papaya seeds also contain the cyanogenic substance prunasin.

Traditional medicine

In some parts of the world, papaya leaves are made into tea as a treatment for malaria, but the mechanism is not understood and no treatment method based on these results has been scientifically proven.

Allergies and side effects

Papaya releases a latex fluid when not ripe, possibly causing irritation and an allergic reaction in some people.

Mango

Mangoes are juicy stone fruit (drupe) from numerous species of tropical trees belonging to the flowering plant genus Mangifera, cultivated mostly for their edible fruit.

The majority of these species are found in nature as wild mangoes. The genus belongs to the cashew family Anacardiaceae. Mangoes are native to South Asia, from where the "common mango" or "Indian mango", Mangifera indica, has been distributed worldwide to become one of the most widely cultivated fruits in the tropics. Other Mangifera species (e.g. horse mango, Mangifera foetida) are grown on a more localized basis.

It is the national fruit of India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, and the national tree of Bangladesh.

Description

Mango trees grow to 35–40 m (115–131 ft) tall, with a crown radius of 10 m (33 ft). The trees are long-lived, as some specimens still fruit after 300 years. In deep soil, the taproot descends to a depth of 6 m (20 ft), with profuse, wide-spreading feeder roots and anchor roots penetrating deeply into the soil. The leaves are evergreen, alternate, simple, 15–35 cm (5.9–13.8 in) long, and 6–16 cm (2.4–6.3 in) broad; when the leaves are young they are orange-pink, rapidly changing to a dark, glossy red, then dark green as they mature. The flowers are produced in terminal panicles 10–40 cm (3.9–15.7 in) long; each flower is small and white with five petals 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long, with a mild, sweet fragrance. Over 500 varieties of mangoes are known, many of which ripen in summer, while some give a double crop. The fruit takes four to five months from flowering to ripen.

The ripe fruit varies in size, shape, color, sweetness, and eating quality Cultivars are variously yellow, orange, red, or green, and carry a single flat, oblong pit that can be fibrous or hairy on the surface, and which does not separate easily from the pulp. The fruits may be somewhat round, oval, or kidney-shaped, ranging from 5–25 centimetres (2–10 in) in length and from 140 grams (5 oz) to 2 kilograms (5 lb) in weight per individual fruit. The skin is leather-like, waxy, smooth, and fragrant, with color ranging from green to yellow, yellow-orange, yellow-red, or blushed with various shades of red, purple, pink or yellow when fully ripe.

Ripe intact mangoes give off a distinctive resinous, sweet smell. Inside the pit 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) thick is a thin lining covering a single seed, 4–7 cm (1.6–2.8 in) long. Mangoes have recalcitrant seeds which do not survive freezing and drying. Mango trees grow readily from seeds, with germination success highest when seeds are obtained from mature fruits.

Etymology and history

The English word "mango" (plural "mangoes" or "mangos") originated from the Malayalam word māṅṅa (or mangga) via Dravidian mankay and Portuguese manga during the spice trade period with South India in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Mango is mentioned by Hendrik van Rheede, the Dutch commander of the Malabar region in his 1678 book, Hortus Malabaricus, about plants having economic value. When mangoes were first imported to the American colonies in the 17th century, they had to be pickled because of lack of refrigeration. Other fruits were also pickled and came to be called "mangoes", especially bell peppers, and in the 18th century, the word "mango" became a verb meaning "to pickle".

Cultivation

Mangoes have been cultivated in South Asia for thousands of years and reached Southeast Asia between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. By the 10th century CE, cultivation had begun in East Africa. The 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta reported it at Mogadishu. Cultivation came later to Brazil, Bermuda, the West Indies, and Mexico, where an appropriate climate allows its growth.

The mango is now cultivated in most frost-free tropical and warmer subtropical climates; almost half of the world's mangoes are cultivated in India alone, with the second-largest source being China. Mangoes are also grown in Andalusia, Spain (mainly in Málaga province), as its coastal subtropical climate is one of the few places in mainland Europe that permits the growth of tropical plants and fruit trees. The Canary Islands are another notable Spanish producer of the fruit. Other cultivators include North America (in South Florida and California's Coachella Valley), South and Central America, the Caribbean, Hawai'i, south, west, and central Africa, Australia, China, South Korea, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Southeast Asia. Though India is the largest producer of mangoes, it accounts for less than 1% of the international mango trade; India consumes most of its own production.

Many commercial cultivars are grafted on to the cold-hardy rootstock of Gomera-1 mango cultivar, originally from Cuba. Its root system is well adapted to a coastal Mediterranean climate. Many of the 1,000+ mango cultivars are easily cultivated using grafted saplings, ranging from the "turpentine mango" (named for its strong taste of turpentine) to the Bullock's Heart. Dwarf or semidwarf varieties serve as ornamental plants and can be grown in containers. A wide variety of diseases can afflict mangoes.

Cultivars

There are many hundreds of named mango cultivars. In mango orchards, several cultivars are often grown in order to improve pollination. Many desired cultivars are monoembryonic and must be propagated by grafting or they do not breed true. A common monoembryonic cultivar is 'Alphonso', an important export product, considered as "the king of mangoes".

Cultivars that excel in one climate may fail elsewhere. For example, Indian cultivars such as 'Julie', a prolific cultivar in Jamaica, require annual fungicide treatments to escape the lethal fungal disease anthracnose in Florida. Asian mangoes are resistant to anthracnose.

The current world market is dominated by the cultivar 'Tommy Atkins', a seedling of 'Haden' that first fruited in 1940 in southern Florida and was initially rejected commercially by Florida researchers. Growers and importers worldwide have embraced the cultivar for its excellent productivity and disease resistance, shelf life, transportability, size, and appealing color. Although the Tommy Atkins cultivar is commercially successful, other cultivars may be preferred by consumers for eating pleasure, such as Alphonso.

Generally, ripe mangoes have an orange-yellow or reddish peel and are juicy for eating, while exported fruit are often picked while underripe with green peels. Although producing ethylene while ripening, unripened exported mangoes do not have the same juiciness or flavor as fresh fruit.

Food

Mangoes are generally sweet, although the taste and texture of the flesh varies across cultivars; some have a soft, pulpy texture similar to an overripe plum, while others are firmer, like a cantaloupe or avocado, and some may have a fibrous texture. The skin of unripe, pickled, or cooked mango can be consumed, but has the potential to cause contact dermatitis of the lips, gingiva, or tongue in susceptible people.

Cuisine

Mangoes are widely used in cuisine. Sour, unripe mangoes are used in chutneys, athanu, pickles side dishes, or may be eaten raw with salt, chili, or soy sauce. A summer drink called aam panna comes from mangoes. Mango pulp made into jelly or cooked with red gram dhal and green chillies may be served with cooked rice. Mango lassi is popular throughout South Asia, prepared by mixing ripe mangoes or mango pulp with buttermilk and sugar. Ripe mangoes are also used to make curries. Aamras is a popular thick juice made of mangoes with sugar or milk, and is consumed with chapatis or pooris. The pulp from ripe mangoes is also used to make jam called mangada. Andhra aavakaaya is a pickle made from raw, unripe, pulpy, and sour mango, mixed with chili powder, fenugreek seeds, mustard powder, salt, and groundnut oil. Mango is also used in Andhra Pradesh to make dahl preparations. Gujaratis use mango to make chunda (a spicy, grated mango delicacy).

Mangoes are used to make murabba (fruit preserves), muramba (a sweet, grated mango delicacy), amchur (dried and powdered unripe mango), and pickles, including a spicy mustard-oil pickle and alcohol. Ripe mangoes are often cut into thin layers, desiccated, folded, and then cut. These bars are similar to dried guava fruit bars available in some countries. The fruit is also added to cereal products such as muesli and oat granola. Mangoes are often prepared charred in Hawaii.

Unripe mango may be eaten with bagoong (especially in the Philippines), fish sauce, vinegar, soy sauce, or with dash of salt (plain or spicy). Dried strips of sweet, ripe mango (sometimes combined with seedless tamarind to form mangorind) are also popular. Mangoes may be used to make juices, mango nectar, and as a flavoring and major ingredient in ice cream and sorbetes.

Mango is used to make juices, smoothies, ice cream, fruit bars, raspados, aguas frescas, pies, and sweet chili sauce, or mixed with chamoy, a sweet and spicy chili paste. It is popular on a stick dipped in hot chili powder and salt or as a main ingredient in fresh fruit combinations. In Central America, mango is either eaten green mixed with salt, vinegar, black pepper, and hot sauce, or ripe in various forms. Toasted and ground pumpkin seed (pepita) with lime and salt are eaten with green mangoes.

Pieces of mango can be mashed and used as a topping on ice cream or blended with milk and ice as milkshakes. Sweet glutinous rice is flavored with coconut, then served with sliced mango as a dessert. In other parts of Southeast Asia, mangoes are pickled with fish sauce and rice vinegar. Green mangoes can be used in mango salad with fish sauce and dried shrimp. Mango with condensed milk may be used as a topping for shaved ice.

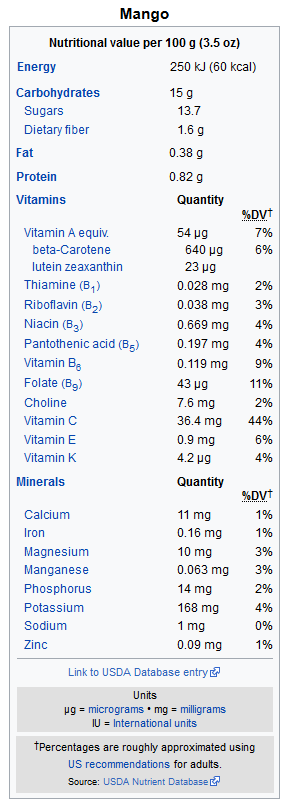

Nutrients

The energy value per 100 g (3.5 oz) serving of the common mango is 250 kJ (60 kcal), and that of the apple mango is slightly higher (330 kJ (79 kcal) per 100 g). Fresh mango contains a variety of nutrients (right table), but only vitamin C and folate are in significant amounts of the Daily Value as 44% and 11%, respectively.

Phytochemicals

Numerous phytochemicals are present in mango peel and pulp, such as the triterpene, lupeol which is under basic research for its potential biological effects. An extract of mango branch bark called Vimang, containing numerous polyphenols, has been studied in elderly humans.

Mango peel pigments under study include carotenoids, such as the provitamin A compound, beta-carotene, lutein and alpha-carotene, and polyphenols, such as quercetin, kaempferol, gallic acid, caffeic acid, catechins and tannins. Mango contains a unique xanthonoid called mangiferin.

Phytochemical and nutrient content appears to vary across mango cultivars. Up to 25 different carotenoids have been isolated from mango pulp, the densest of which was beta-carotene, which accounts for the yellow-orange pigmentation of most mango cultivars. Mango leaves also have significant polyphenol content, including xanthonoids, mangiferin and gallic acid.

The pigment euxanthin, known as Indian yellow, is often thought to be produced from the urine of cattle fed mango leaves; the practice is described as having been outlawed in 1908 because of malnutrition of the cattle and possible urushiol poisoning. This supposed origin of euxanthin appears to rely on a single, anecdotal source, and Indian legal records do not outlaw such a practice.

Flavor

The flavor of mango fruits is constituted by several volatile organic chemicals mainly belonging to terpene, furanone, lactone, and ester classes. Different varieties or cultivars of mangoes can have flavor made up of different volatile chemicals or same volatile chemicals in different quantities. In general, New World mango cultivars are characterized by the dominance of δ-3-carene, a monoterpene flavorant; whereas, high concentration of other monoterpenes such as (Z)-ocimene and myrcene, as well as the presence of lactones and furanones, is the unique feature of Old World cultivars. In India, 'Alphonso' is one of the most popular cultivars. In 'Alphonso' mango, the lactones and furanones are synthesized during ripening; whereas terpenes and the other flavorants are present in both the developing (immature) and ripening fruits. Ethylene, a ripening-related hormone well known to be involved in ripening of mango fruits, causes changes in the flavor composition of mango fruits upon exogenous application, as well. In contrast to the huge amount of information available on the chemical composition of mango flavor, the biosynthesis of these chemicals has not been studied in depth; only a handful of genes encoding the enzymes of flavor biosynthetic pathways have been characterized to date.

Potential for contact dermatitis

Contact with oils in mango leaves, stems, sap, and skin can cause dermatitis and anaphylaxis in susceptible individuals. Those with a history of contact dermatitis induced by urushiol (an allergen found in poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac) may be most at risk for mango contact dermatitis. Cross-reactions may occur between mango allergens and urushiol. During the primary ripening season of mangoes, contact with mango plant parts is the most common cause of plant dermatitis in Hawaii. However, sensitized individuals are still able to safely eat peeled mangos or drink mango juice.

Cultural significance

The mango is the national fruit of India, Pakistan, and the Philippines. It is also the national tree of Bangladesh. In India, harvest and sale of mangoes is during March–May and this is annually covered by news agencies.

The Mughal emperor Akbar (1556–1605 ) is said to have planted a mango orchard having 100,000 trees in Darbhanga, eastern India.[64] The Jain goddess Ambika is traditionally represented as sitting under a mango tree. In Hinduism, the perfectly ripe mango is often held by Lord Ganesha as a symbol of attainment, regarding the devotees' potential perfection. Mango blossoms are also used in the worship of the goddess Saraswati. No Telugu/Kannada New Year's Day called Ugadi passes without eating ugadi pachadi made with mango pieces as one of the ingredients.

Dried mango skin and its seeds are also used in Ayurvedic medicines. Mango leaves are used to decorate archways and doors in Indian houses and during weddings and celebrations such as Ganesh Chaturthi. Mango motifs and paisleys are widely used in different Indian embroidery styles, and are found in Kashmiri shawls, Kanchipuram silk sarees, etc. Paisleys are also common to Iranian art, because of its pre-Islamic Zoroastrian past.

In Andhra Pradesh, mango leaves are considered auspicious and are used to decorate front doors during festivals.

In Tamil Nadu, the mango is referred to as one of the three royal fruits, along with banana and jackfruit, for their sweetness and flavor. This triad of fruits is referred to as ma-pala-vazhai.

Fruit drinks that include mango are popular in India, with brands such as Frooti, Maaza, and Slice. These leading brands include sugar and artificial flavors, so they do not qualify as "juice" under Food Safety and Standards Authority of India regulations.

In the West Indies, the expression "to go mango walk" means to steal another person's mango fruits. This is celebrated in the famous song, "The Mango Walk".

In Australia, the first tray of mangoes of the season is traditionally sold at an auction for charity.

The classical Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa sang the praises of mangoes.

Mangoes, although they were almost unheard of in China before, were popularized during the Cultural Revolution as symbols of Chairman Mao Zedong's love for the people.

Ginger

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or simply ginger, is widely used as a spice or a folk medicine.

It is a herbaceous perennial which grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of leaves) about a meter tall bearing narrow leaf blades. The inflorescences bear pale yellow with purple flowers and arise directly from the rhizome on separate shoots. Ginger is in the family Zingiberaceae, to which also belong turmeric (Curcuma longa), cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum), and galangal. Ginger originated in the tropical rainforests from the Indian subcontinent to Southern Asia where ginger plants show considerable genetic variation. As one of the first spices exported from the Orient, ginger arrived in Europe during the spice trade, and was used by ancient Greeks and Romans. The distantly related dicots in the genus Asarum are commonly called wild ginger because of their similar taste.

Etymology

The English origin of the word, "ginger", is from the mid-14th century, from Old English gingifer, from Medieval Latin gingiber, from Greek zingiberis, from Prakrit (Middle Indic) singabera, from Sanskrit srngaveram, from srngam "horn" and vera- "body", from the shape of its root. The word probably was readopted in Middle English from Old French gingibre (modern French gingembre).

Origin and distribution

Ginger likely originated as ground flora of tropical lowland forests in regions from the Indian subcontinent to southern Asia, where its cultivation remains among the world's largest producers, including India, China, and other countries of southern Asia (see Production). Numerous wild relatives are still found in these regions, and in tropical or subtropical world regions, such as Hawaii, Japan, Australia, and Malaysia.

Horticulture

Ginger produces clusters of white and pink flower buds that bloom into yellow flowers. Because of its aesthetic appeal and the adaptation of the plant to warm climates, it is often used as landscaping around subtropical homes. It is a perennial reed-like plant with annual leafy stems, about a meter (3 to 4 feet) tall. Traditionally, the rhizome is gathered when the stalk withers; it is immediately scalded, or washed and scraped, to kill it and prevent sprouting. The fragrant perisperm of the Zingiberaceae is used as sweetmeats by Bantu, and also as a condiment and sialagogue.

Uses

Ginger produces a hot, fragrant kitchen spice. Young ginger rhizomes are juicy and fleshy with a mild taste. They are often pickled in vinegar or sherry as a snack or cooked as an ingredient in many dishes. They can be steeped in boiling water to make ginger herb tea, to which honey may be added. Ginger can be made into candy or ginger wine.

Mature ginger rhizomes are fibrous and nearly dry. The juice from ginger roots is often used as a seasoning in Indian recipes and is a common ingredient of Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and many South Asian cuisines for flavoring dishes such as seafood, meat, and vegetarian dishes.

Fresh ginger can be substituted for ground ginger at a ratio of six to one, although the flavors of fresh and dried ginger are somewhat different. Powdered dry ginger root is typically used as a flavoring for recipes such as gingerbread, cookies, crackers and cakes, ginger ale, and ginger beer. Candied ginger, or crystallized ginger, is the root cooked in sugar until soft, and is a type of confectionery. Fresh ginger may be peeled before eating. For longer-term storage, the ginger can be placed in a plastic bag and refrigerated or frozen.

Regional uses

In Indian cuisine, ginger is a key ingredient, especially in thicker gravies, as well as in many other dishes, both vegetarian and meat-based. Ginger also has a role in traditional Ayurvedic medicine. It is an ingredient in traditional Indian drinks, both cold and hot, including spiced masala chai. Fresh ginger is one of the main spices used for making pulse and lentil curries and other vegetable preparations. Fresh ginger together with peeled garlic cloves is crushed or ground to form ginger garlic masala. Fresh, as well as dried, ginger is used to spice tea and coffee, especially in winter. In south India, "sambharam" is a summer yogurt drink made with ginger as a key ingredient, along with green chillies, salt and curry leaves. Ginger powder is used in food preparations intended primarily for pregnant or nursing women, the most popular one being katlu, which is a mixture of gum resin, ghee, nuts, and sugar. Ginger is also consumed in candied and pickled form. In Japan, ginger is pickled to make beni shoga and gari or grated and used raw on tofu or noodles. It is made into a candy called shoga no sato zuke. In the traditional Korean kimchi, ginger is either finely minced or just juiced to avoid the fibrous texture and added to the ingredients of the spicy paste just before the fermenting process.

In Burma, ginger is called gyin. It is widely used in cooking and as a main ingredient in traditional medicines. It is consumed as a salad dish called gyin-thot, which consists of shredded ginger preserved in oil, with a variety of nuts and seeds. In Thailand' where it is called ขิง khing, it is used to make a ginger garlic paste in cooking. In Indonesia, a beverage called wedang jahe is made from ginger and palm sugar. Indonesians also use ground ginger root, called jahe, as a common ingredient in local recipes. In Malaysia, ginger is called halia and used in many kinds of dishes, especially soups. Called luya in the Philippines, ginger is a common ingredient in local dishes and is brewed as a tea called salabat. In Vietnam, the fresh leaves, finely chopped, can be added to shrimp-and-yam soup (canh khoai mỡ) as a top garnish and spice to add a much subtler flavor of ginger than the chopped root. In China, sliced or whole ginger root is often paired with savory dishes such as fish, and chopped ginger root is commonly paired with meat, when it is cooked. Candied ginger is sometimes a component of Chinese candy boxes, and a herbal tea can be prepared from ginger.

In the Caribbean, ginger is a popular spice for cooking and for making drinks such as sorrel, a drink made during the Christmas season. Jamaicans make ginger beer both as a carbonated beverage and also fresh in their homes. Ginger tea is often made from fresh ginger, as well as the famous regional specialty Jamaican ginger cake. On the island of Corfu, Greece, a traditional drink called τσιτσιμπύρα (tsitsibira), a type of ginger beer, is made. The people of Corfu and the rest of the Ionian islands adopted the drink from the British, during the period of the United States of the Ionian Islands.

In Western cuisine, ginger is traditionally used mainly in sweet foods such as ginger ale, gingerbread, ginger snaps, parkin, and speculaas. A ginger-flavored liqueur called Canton is produced in Jarnac, France. Ginger wine is a ginger-flavored wine produced in the United Kingdom, traditionally sold in a green glass bottle. Ginger is also used as a spice added to hot coffee and tea.

Similar ingredients

Myoga (Zingiber mioga 'Roscoe') appears in Japanese cuisine; the flower buds are the part eaten.

Another plant in the Zingiberaceae family, galangal, is used for similar purposes as ginger in Thai cuisine. Galangal is also called Thai ginger, fingerroot (Boesenbergia rotunda), Chinese ginger, or the Thai krachai.

A dicotyledonous native species of eastern North America, Asarum canadense, is also known as "wild ginger", and its root has similar aromatic properties, but it is not related to true ginger. The plant contains aristolochic acid, a carcinogenic compound.[12] The United States Food and Drug Administration warns that consumption of aristolochic acid-containing products is associated with "permanent kidney damage, sometimes resulting in kidney failure that has required kidney dialysis or kidney transplantation. In addition, some patients have developed certain types of cancers, most often occurring in the urinary tract."[12]

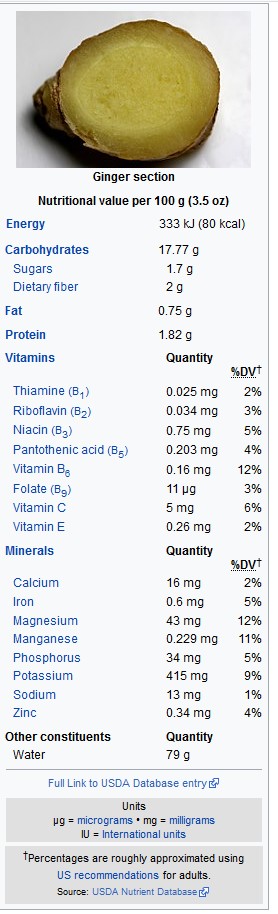

Nutritional information

Raw ginger is composed of 79% water, 18% carbohydrates, 2% protein, and 1% fat (table). In 100 grams (a standard amount used to compare with other foods), raw ginger supplies 80 Calories and contains moderate amounts of vitamin B6 (12% of the Daily Value, DV) and the dietary minerals, magnesium (12% DV) and manganese (11% DV), but otherwise is low in nutrient content (table).

When used as a spice powder in a common serving amount of one US tablespoon (5 grams), ground dried ginger (9% water) provides negligible content of essential nutrients, with the exception of manganese (70% DV).

Composition and safety

If consumed in reasonable quantities, ginger has few negative side effects. It is on the FDA's "generally recognized as safe" list, though it does interact with some medications, including the anticoagulant drug warfarin and the cardiovascular drug, nifedipine.

Chemistry

The characteristic fragrance and flavor of ginger result from volatile oils that compose 1-3% of the weight of fresh ginger, primarily consisting of zingerone, shogaols and gingerols with gingerol (1-[4'-hydroxy-3'-methoxyphenyl]-5-hydroxy-3-decanone) as the major pungent compound. Zingerone is produced from gingerols during drying, having lower pungency and a spicy-sweet aroma.

Medicinal use and research

As the evidence that ginger helps alleviate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting is inconclusive, it is not recommended for any clinical uses or for nausea. There is no clear evidence of harm from taking ginger during pregnancy, although its safety has not been established.

Allergic reactions to ginger generally result in a rash.Although generally recognized as safe, ginger can cause heartburn and other side effects, particularly if taken in powdered form. Unchewed fresh ginger may result in intestinal blockage, and individuals who have had ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, or blocked intestines may react badly to large quantities of fresh ginger. It can also adversely affect individuals with gallstones and may interfere with the effects of anticoagulants, such as warfarin or aspirin.

Ginger is not effective for treating dysmenorrhea, and there is no evidence for it having analgesic properties.